The goal of this page is to understand why existing code has been written this way, and how to write new code that fits in with the old one.

Tree structure

Electron apps have two sides: what happens in the browser (node.js) process,

and what happens in the renderer (chromium) process.

In itch, things that happen on the browser/node side are:

- itch.io API requests

- Installing dependencies (unarchiver, for example)

- Driving downloads with butler

- Launching applications

- Showing native notifications, interacting with the OS shell, etc.

Things that happen on the renderer/chromium-content side:

- Rendering the whole user interface

- Showing HTML5 notifications

These used to be separated in the source tree, but they no longer are, because it's useful to share code between them sometimes (with two copies, one on each side).

Since the redux rewrite, there's only a single store per process: the browser store is the reference one, and it sends diffs to all renderer processes so that they're all kept in sync, using redux-electron-store.

Building

Sources are in appsrc and testsrc, compiled javascript files are

in app, and test.

Grunt drives the build process:

- the

copytask copies some files as-is (example:testsrc/runner) - the

sasstask compiles SCSS into CSS - the

tstask compiles TypeScript into ES6 that Chrome & node.js understand

There's newer variants of some tasks (newer:sass) which

only recompile required files — those are the default grunt task.

The recommended workflow is simply to edit files in appsrc and testsrc,

and start the app with npm start. It calls the necessary grunt tasks, and

starts electron for you.

TypeScript usage and features

We try to use recent versions of TypeScript, to take advante of new features.

Async/await

We use TypeScript's async/await support to be able to write code that translates to coroutines:

Conceptually, it lets us write this:

function installSoftware (name: string) {

return download(name)

.then(() => extract(name))

.then(() => verify(name))

.catch((err) => {

// Uh oh, something happened

});

}...but like this:

async function installSoftware (name: string) {

try {

await download(name);

await extract(name);

await verify(name);

} catch (err) {

// Uh oh, something happened

}

}Code style

We abide by a pretty standard TSLint (by ) rules file, except:

object-literal-sort-keysis disabled because OCD doesn't make software betterno-require-importsis disabled because some node modules don't play well without it (might be solved by better typings / use of TypeScript namespaces)

Every CI build checks the code for conformance.

You can also run it manually on your machine with npm run lint.

Additionally, some editors have plug-ins to support real-time linting:

- Visual Studio Code has a

TSLintextension that does the job just fine.

Casing

camelCase is used throughout the project, even though the itch.io

backend uses snake_case internally. As a result, for example,

API responses are normalized to camelCase.

Notable exceptions include:

- SCSS variables, classes and partials are

kebab-case Source files are

kebab-case- e.g. the

GridItemcontent would live ingrid-item.js

- e.g. the

i18n keys are

snake_casefor historical reasons

Testing

npm test is a bit sluggish, because it uses nyc to register code

coverage. It also runs a full linting of the source code.

The test harness we use is a spruced-up version of substack/tape, named zopf. It's basically the same except you can define cases, like so:

import test from "zopf";

test("light tests", t => {

t.case("in the dark", t => {

// ... test things

})

t.case("in broad daylight", t => {

// ... test things

})

t.case("whilst holding your hand", t => {

// ... test things

})

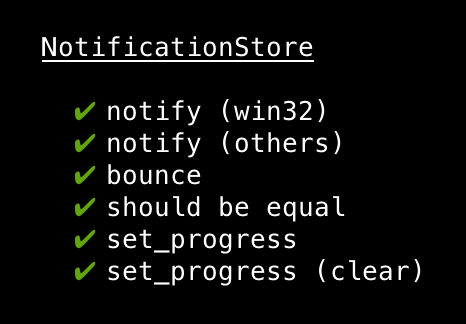

})Cases run in-order and produce pretty output via tap-spec, like this:

Also, test cases can be asynchronous:

import test from "zopf"

test("filesystem stuff", t => {

t.case("can touch and unlink", async t => {

const file = "tmp/some_file";

await myfs.touch(file);

t.ok(await myfs.exists(file), "exists after being touched");

await myfs.unlink(file);

t.notOk(await myfs.exists(file), "no longer exists after unlink");

})

})import, export, modules, require

Since we now use TypeScript's import and export support, faking modules has become

a bit trickier. Basically, the canonical way to get the default export of a module

is now this:

// preferred way

import mymodule from "./my-module";

// sometimes required when the module needs to be required at a precise

// point in time because of side-effects

const mymodule = require("./my-module").default;Two other tools we use heavily in tests are proxyquire, to provide fake

versions of modules, and sinon, to create spies/stubs/mocks. They're both

pretty solid libraries, and together with tape

React components

Follow redux conventions, look at appsrc/components/icon.tsx for a good example.

We have our own connect which provides props.t for i18n, and we

usually export the un-connected class too, for testing.

CSS

Our CSS is a bit of a wasteland for now, it could use a good cleanup and better documentation.